Capital accumulation

| Economics |

|

Economies by region

|

| General categories |

|---|

|

History of economic thought Methodology · Mainstream & heterodox |

| Technical methods |

|

Game theory · Optimization Computational · Econometrics Experimental · National accounting |

| Fields and subfields |

|

Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary |

| Lists |

|

Journals · Publications |

| Business and Economics Portal |

The accumulation of capital refers to the gathering or amassing of objects of value; the increase in wealth through concentration; or the creation of wealth. Capital is money or a financial asset invested for the purpose of making more money (whether in the form of profit, rent, interest, royalties, capital gain or some other kind of return).[1] This activity forms the basis of the economic system of capitalism, where economic activity is structured around the accumulation of capital (investment in production in order to realize a financial profit).

Human capital may also be seen as a form of capital: investment in one's personal abilities, such as through education, to improve their function and therefore capital accumulation (wealth) in a market economy.

Definition

The definition of capital accumulation is subject to controversy and ambiguities, because it could refer to a net addition to existing wealth, or to a redistribution of wealth. If more wealth is produced than there was before, a society becomes richer; the total stock of wealth increases. But if some accumulate capital only at the expense of others, wealth is merely shifted from A to B. In principle, it is possible that a few people or organisations accumulate capital and grow richer, although the total stock of wealth of society decreases.But it should be noticed that capital may increase by increasing the total wealth of society but few people grow richer while most of the people grow comparatively poorer. That is actually the tendency of the capital accumulation discovered by Marx.[2] Most often, capital accumulation involves both a net addition and a redistribution of wealth, which may raise the question of who really benefits from it most.

In economics, accounting and Marxian economics, capital accumulation is often equated with investment of profit income or savings, especially in real capital goods. The concentration and centralisation of capital are two of the results of such accumulation (see below).

But capital accumulation can refer variously to

- real investment in tangible means of production.

- financial investment in assets represented on paper, yielding profit, interest, rent, royalties, fees or capital gains.

- investment in non-productive physical assets such as residential real estate or works of art that appreciate in value.

- "human capital accumulation", i.e., new education and training increasing the skills of the (potential) labour force which can increase earnings from work.

Non-financial and financial capital accumulation is usually needed for economic growth, since additional production usually requires additional funds to enlarge the scale of production. Smarter and more productive organization of production can also increase production without increased capital. Capital can be created without increased investment by inventions or improved organization that increase productivity, discoveries of new assets (oil, gold, minerals, etc.), the sale of property, etc.

In modern macroeconomics and econometrics the term capital formation is often used in preference to "accumulation", though the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) refers nowadays to "accumulation". The term is occasionally used in national accounts.

The measurement of accumulation

Accumulation can be measured as the monetary value of investments, the amount of income that is reinvested, or as the change in the value of assets owned (the increase in the value of the capital stock). Using company balance sheets, tax data and direct surveys as a basis, government statisticians estimate total investments and assets for the purpose of national accounts, national balance of payments and flow of funds statistics. Usually the Reserve Banks and the Treasury provide interpretations and analysis of this data. Standard indicators include Capital formation, Gross fixed capital formation, fixed capital, household asset wealth, and foreign direct investment.

Organisations such as the International Monetary Fund, UNCTAD, the World Bank Group, the OECD, and the Bank for International Settlements used national investment data to estimate world trends. The Bureau of Economic Analysis, Eurostat and the Japan Statistical Office provide data on the USA, Europe and Japan respectively.

Other useful sources of investment information are business magazines such as Fortune, Forbes, The Economist, Business Week, etc., and various corporate "watchdog" organisations and non-governmental organization publications. A reputable scientific journal is the Review of Income & Wealth. In the case of the USA, the "Analytical Perspectives" document (an annex to the yearly budget) provides useful wealth and capital estimates applying to the whole country.

Harrod–Domar model

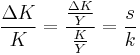

In macroeconomics, following the Harrod–Domar model, the savings ratio ( ) and the capital coefficient (

) and the capital coefficient ( ) are regarded as critical factors for accumulation and growth, assuming that all saving is used to finance fixed investment. The rate of growth of the real stock of fixed capital (

) are regarded as critical factors for accumulation and growth, assuming that all saving is used to finance fixed investment. The rate of growth of the real stock of fixed capital ( ) is:

) is:

where  is the real national income. If the capital-output ratio or capital coefficient (

is the real national income. If the capital-output ratio or capital coefficient ( ) is constant, the rate of growth of

) is constant, the rate of growth of  is equal to the rate of growth of

is equal to the rate of growth of  . This is determined by

. This is determined by  (the ratio of net fixed investment or saving to

(the ratio of net fixed investment or saving to  ) and

) and  .

.

A country might for example save and invest 12% of its national income, and then if the capital coefficient is 4:1 (i.e. $4 billion must be invested to increase the national income by 1 billion) the rate of growth of the national income might be 3% annually. However, as Keynesian economics points out, savings do not automatically mean investment (as liquid funds may be hoarded for example). Investment may also not be investment in fixed capital (see above).

Assuming that the turnover of total production capital invested remains constant, the proportion of total investment which just maintains the stock of total capital, rather than enlarging it, will typically increase as the total stock increases. The growth rate of incomes and net new investments must then also increase, in order to accelerate the growth of the capital stock. Simply put, the bigger capital grows, the more capital it takes to keep it growing and the more markets must expand.

Marxian concept of capital accumulation

| Part of a series on |

|

Concepts

Economic theories

Origins

People

Variants

Related topics

Movements

Capitalism Portal |

In Karl Marx's economic theory, capital accumulation refers to the operation whereby profits are reinvested increasing the total quantity of capital. Capital is viewed by Marx as expanding value, that is, in other terms, as a sum of money that is transformed into a larger sum of money. (Capitalism is this money-making activity, although Marxists often equate capitalism with the capitalist mode of production). Here, capital is defined essentially as economic or commercial asset value in search of additional value or surplus-value. This requires property relations which enable objects of value to be appropriated and owned, and trading rights to be established.

According to Marx, capital accumulation has a double origin, namely in trade and in expropriation, both of a legal or illegal kind. The reason is that a stock of capital can be increased through a process of exchange or "trading up" but also through directly taking an asset or resource from someone else, without compensation. David Harvey calls this accumulation by dispossession. Marx does not discuss gifts and grants as a source of capital accumulation, nor does he analyze taxation in detail. Nowadays the tax take is often so large (i.e., 25-40% of GDP) that some authors refer to state capitalism. This gives rise to a proliferation of tax havens to evade tax liability.

The continuation and progress of capital accumulation depends on the removal of obstacles to the expansion of trade, and this has historically often been a violent process. As markets expand, more and more new opportunities develop for accumulating capital, because more and more types of goods and services can be traded in. But capital accumulation may also confront resistance, when people refuse to sell, or refuse to buy (for example a strike by investors or workers, or consumer resistance). What spurs accumulation is competition; in business, if you don't go forward, you go backward, and unless the law prevents it, the strong will exploit the weak.

In general, Marx's critique of capital accumulation is that the human chase after wealth and self-enrichment leads to inhuman consequences. The enrichment of some is at the expense of the immiseration of others, and competition becomes brutal. The basis of it all is the exploitation of the labour effort of others. When the "economic cake" expands, this may be obscured because all can gain from trade. But when the "economic cake" shrinks, then capital accumulation can only occur by taking income or assets from other people, other social classes, or other nations. The point is that to exist, capital must always grow, and to ensure that it will grow, people are prepared to do almost anything.

The hypothetical system of socialism would succeed capitalism as the dominant mode of production when the accumulation of capital can no longer sustain itself due to falling rates of profit in real production relative to increasing productivity. A socialist economy would not base production on the accumulation of capital, but would instead base production and economic activity on the criteria of satisfying human needs - that is, production would be carried out directly for use.

Concentration and centralization

According to Marx, capital has the tendency for concentration and centralization the hands of richest capitalists. Marx explains:

"It is concentration of capitals already formed, destruction of their individual independence, expropriation of capitalist by capitalist, transformation of many small into few large capitals.... Capital grows in one place to a huge mass in a single hand, because it has in another place been lost by many.... The battle of competition is fought by cheapening of commodities. The cheapness of commodities demands, caeteris paribus, on the productiveness of labour, and this again on the scale of production. Therefore, the larger capitals beat the smaller. It will further be remembered that, with the development of the capitalist mode of production, there is an increase in the minimum amount of individual capital necessary to carry on a business under its normal conditions. The smaller capitals, therefore, crowd into spheres of production which Modern Industry has only sporadically or incompletely got hold of. Here competition rages.... It always ends in the ruin of many small capitalists, whose capitals partly pass into the hands of their conquerors, partly vanish."[3]

The rate of accumulation

In Marxian economics, the rate of accumulation is defined as (1) the value of the real net increase in the stock of capital in an accounting period, (2) the proportion of realised surplus-value or profit-income which is reinvested, rather than consumed. This rate can be expressed by means of various ratios between the original capital outlay, the realised turnover, surplus-value or profit and reinvestments (see, e.g., the writings of the economist Michal Kalecki).

Other things being equal, the greater the amount of profit-income that is disbursed as personal earnings and used for consumptive purposes, the lower the savings rate and the lower the rate of accumulation is likely to be. However, earnings spent on consumption can also stimulate market demand and higher investment. This is the cause of endless controversies in economic theory about "how much to spend, and how much to save".

In a boom period of capitalism, the growth of investments is cumulative, i.e. one investment leads to another, leading to a constantly expanding market, an expanding labor force, and an increase in the standard of living for the majority of the people.

In a stagnating, decadent capitalism, the accumulation process is increasingly oriented towards investment on military and security forces, real estate, financial speculation, and luxury consumption. In that case, income from value-adding production will decline in favour of interest, rent and tax income, with as a corollary an increase in the level of permanent unemployment.

As a rule, the larger the total sum of capital invested, the higher the return on investment will be. The more capital one owns, the more capital one can also borrow and reinvest at a higher rate of profit or interest. The inverse is also true, and this is one factor in the widening gap between the rich and the poor.

Ernest Mandel emphasized that the rhythm of capital accumulation and growth depended critically on (1) the division of a society's social product between "necessary product" and "surplus product", and (2) the division of the surplus product between investment and consumption. In turn, this allocation pattern reflected the outcome of competition among capitalists, competition between capitalists and workers, and competition between workers. The pattern of capital accumulation can therefore never be simply explained by commercial factors, it also involved social factors and power relationships.

The circuit of capital accumulation from production

Strictly speaking, capital has accumulated only when realised profit income has been reinvested in capital assets. But the process of capital accumulation in production has, as suggested in the first volume of Marx's Das Kapital, at least 7 distinct but linked moments:

- The initial investment of capital (which could be borrowed capital) in means of production and labor power.

- The command over surplus-labour and its appropriation.

- The valorisation (increase in value) of capital through production of new outputs.

- The appropriation of the new output produced by employees, containing the added value.

- The realisation of surplus-value through output sales.

- The appropriation of realised surplus-value as (profit) income after deduction of costs.

- The reinvestment of profit income in production.

All of these moments do not refer simply to an "economic" or commercial process. Rather, they assume the existence of legal, social, cultural and economic power conditions, without which creation, distribution and circulation of the new wealth could not occur. This becomes especially clear when the attempt is made to create a market where none exists, or where people refuse to trade.

In fact Marx suggests that the original or primitive accumulation of capital often occurs through violence, plunder, slavery, robbery, extortion and theft. He argues that the capitalist mode of production requires that people must be forced to work in value-adding production for someone else, and for this purpose, they must be cut off from sources of income other than selling their labor power.

Simple and expanded reproduction

In volume 2 of Das Kapital, Marx continues the story and shows that, with the aid of bank credit, capital in search of growth can more or less smoothly mutate from one form to another, alternately taking the form of money capital (liquid deposits, securities, etc.), commodity capital (tradeable products, real estate etc.), or production capital (means of production and labor power).

His discussion of the simple and expanded reproduction of the conditions of production offers a more sophisticated model of the parameters of the accumulation process as a whole. At simple reproduction, a sufficient amount is produced to sustain society at the given living standard; the stock of capital stays constant. At expanded reproduction, more product-value is produced than is necessary to sustain society at a given living standard (a surplus product; the additional product-value is available for investments which enlarge the scale and variety of production.

The bourgeois claim there is no economic law according to which capital is necessarily re-invested in the expansion of production, that such depends on anticipated profitability, market expectations and perceptions of investment risk. Such statements only explain the subjective experiences of investors and ignore the objective realities which would influence such opinions. As Marx states in Vol.2, simple reproduction only exists if the variable and surplus capital realized by Dept. 1 - producers of means of production- exactly equals that of the constant capital of Dept. 2, producers of articles of consumption (pg 524). Such equilibrium rests on various assumptions, such as a constant labor supply (no population growth). Accumulation does not imply a necessary change in total magnitude of value produced but can simply refer to a change in the composition of an industry (pg. 514).

Ernest Mandel introduced the additional concept of contracted economic reproduction, i.e. reduced accumulation where business operating at a loss outnumbers growing business, or economic reproduction on a decreasing scale, for example due to wars, natural disasters or devalorisation.

Balanced economic growth requires that different factors in the accumulation process expand in appropriate proportions. But markets themselves cannot spontaneously create that balance, in fact what drives business activity is precisely the imbalances between supply and demand: inequality is the motor of growth. This partly explains why the worldwide pattern of economic growth is very uneven and unequal, even although markets have existed almost everywhere for a very long time. Some people argue that it also explains government regulation of market trade and protectionism.

Capital accumulation as social relation

"Accumulation of capital" sometimes also refers in Marxist writings to the reproduction of capitalist social relations (institutions) on a larger scale over time, i.e., the expansion of the size of the proletariat and of the wealth owned by the bourgeoisie.

This interpretation emphasizes that capital ownership, predicated on command over labor, is a social relation: the growth of capital implies the growth of the working class (a "law of accumulation"). In the first volume of Das Kapital Marx had illustrated this idea with reference to Edward Gibbon Wakefield's theory of colonisation:

"...Wakefield discovered that in the Colonies, property in money, means of subsistence, machines, and other means of production, does not as yet stamp a man as a capitalist if there be wanting the correlative — the wage-worker, the other man who is compelled to sell himself of his own free-will. He discovered that capital is not a thing, but a social relation between persons, established by the instrumentality of things. Mr. Peel, he moans, took with him from England to Swan River, West Australia, means of subsistence and of production to the amount of £50,000. Mr. Peel had the foresight to bring with him, besides, 3,000 persons of the working-class, men, women, and children. Once arrived at his destination, “Mr. Peel was left without a servant to make his bed or fetch him water from the river.” Unhappy Mr. Peel, who provided for everything except the export of English modes of production to Swan River!"

In the third volume of Das Kapital, Marx refers to the "fetishism of capital" reaching its highest point with interest-bearing capital, because now capital seems to grow of its own accord without anybody doing anything. In this case,

"The relations of capital assume their most externalised and most fetish-like form in interest-bearing capital. We have here

, money creating more money, self-expanding value, without the process that effectuates these two extremes. In merchant's capital,

, there is at least the general form of the capitalistic movement, although it confines itself solely to the sphere of circulation, so that profit appears merely as profit derived from alienation; but it is at least seen to be the product of a social relation, not the product of a mere thing. (...) This is obliterated in

, the form of interest-bearing capital. (...) The thing (money, commodity, value) is now capital even as a mere thing, and capital appears as a mere thing. The result of the entire process of reproduction appears as a property inherent in the thing itself. It depends on the owner of the money, i.e., of the commodity in its continually exchangeable form, whether he wants to spend it as money or loan it out as capital. In interest-bearing capital, therefore, this automatic fetish, self-expanding value, money generating money, are brought out in their pure state and in this form it no longer bears the birth-marks of its origin. The social relation is consummated in the relation of a thing, of money, to itself. - Instead of the actual transformation of money into capital, we see here only form without content."

Psychology, sociology and ethics of capital accumulation

There have been numerous psychological and sociological studies of the motivations of investment behaviour by individuals. Most of these suggest that the propensity to accumulate capital is associated with qualities such as an intelligent understanding of property ownership, a positive attitude towards money, the ability to seize a money-making opportunity, and a desire to acquire more wealth. Like so many things human, some theorists regard these qualities as innate and genetic qualities, while others regard them as learned through social experience; some theorists think that both biological and social factors are involved.

However, even if a strong motivation for enrichment or social improvement exists, the business, government, legal, climate, local culture or social instability may prevent this motivation from being realised. Hernando de Soto for example argues that the reason why poor countries are poor is mainly because of the absence of a legal-cultural infrastructure of "asset management" and of formalised and enforced private property rights. Many systems seemed designed to keep a small minority in power so they can consume more. This power minority takes advantage of the common people—consuming much more than they produce. One popular argument in this respect remains the vicious cycle of poverty: the poor are poor because they are poor. Critics of this argument object it is an uninformative and unhelpful tautology.

Greed and desire can play a very important role in capital accumulation, but are not a necessary requirement. Indeed according to Max Weber's study of capitalism and the Protestant ethic, frugality, sobriety, deferred consumption and saving were among the key values of the rising bourgeoisie in the age of the Reformation.

Some economic historians (e.g., David Landes, Gregory Clark (economist)) refer to national psychology and argue that some nations or cultures (e.g., Europe) are inherently better equipped for capital accumulation, due to cultural habits, customs and values.

Other economic historians (e.g. Paul A. Baran) have argued that psychological factors explain very little, because a nation which previously had a low level of accumulation can suddenly "take off". In that case, the causes must be sought in the prevailing social relations.

Controversies about the ethics of accumulation have occurred ever since commercial trade began. If informal and formal prostitution is regarded as the oldest profession, the first ethical debate about accumulation must have occurred tens of thousands of years ago at the very least. The problem is that trade or market forces do not create any particular morality of their own, beyond the requirement to meet contractual obligations that settle transactions. Some forms of trade may be accepted, others rejected, but there exists no general moral principle for this which can be derived from the trade itself.

A good contemporary illustration of this problem is the gigantic increase in total reported crime and the grey economy or shadow economy after the deregulation of world markets from the 1980s, and the marketisation of the USSR and China. But ancient philosophers and theologians already knew about the problem, which is why they were intensely preoccupied with the politics of the “rule of law” and its enforcement.

The main ethical questions concern which routes to wealth are morally justifiable, and what entitles individuals and groups to appropriate amounts of wealth, in particular wealth which they have not themselves created. The medieval economists invented theories of a just price and the moral debate surfaces again these days, e.g., in the controversies about fair trade, imperialism and Islamic banking. Neo-liberal theory emphasises that a "good" person is one who creates new wealth by deferring consumption or improving production, while socialis] theory says a "good" person should be forced to share their wealth however accumulated. The most popular moral theories are similar to that of John Rawls.

Karl Marx illustrated his analysis with sarcastic comments about “Christian accumulation”; some forms of accumulation were believed to be compatible with Jesus Christ, while others were not; some forms of accumulation were forgiven by God afterwards, others were not. Martin Luther for example raged against usury and extortion.

Marxism-Leninism is hostile to all private property and market activity. It must be kept in mind that the "private property" that Marx refers to is the ownership of the means of production by a generally small elite of wealthy entrepreneurs. The proletariat, or laborer, is inferior to all aspects of production—including labor, the products or services made, and revenue; and therefore the division of labor and its products must be equally redistributed to avoid the control and degradation of an unknown bourgeoisie.

But because capital accumulation does not presuppose any particular or specific "moral system", accumulation can also continue regardless of any particular morality advocated by popes, presidents, queens, journalists, pop stars, business tycoons or anybody else. All that is required is (1) the ability to own assets and trade in them and (2) sufficient income beyond subsistence and (3) the will to defer consumption to be able to accumulate capital.

Different forms of capital accumulation

Essentially, in capitalism the production of output depends on the accumulation of capital. The propensity to invest in production therefore depends a lot on expectations of profitability and sales volume, and on perceptions of market risk. If production stops being profitable, or if sales drop sharply, or if there is social instability, capital will exit more and more from the sphere of production. Or if it cannot or does not, rationalisation investments will be undertaken, to amalgamate unprofitable enterprises into profitable units.

As a corollary, capital accumulation may be the accumulation of production capital (industrial assets), or the accumulation of money capital (financial assets), or the accumulation of commodity capital (products, real estate etc. which can be traded).

But irrespective of whether the additional capital value (or surplus-value happens to take the form of profit, interest, rent, or some kind of tax impost or royalty income, what drives the accumulation process is the perpetual search for more surplus-value, for added value as such.

This requires a constant supply of a labor force which can conserve and add value to inputs and capital assets, and thus create a higher value. Normally, the socio-economic compulsion to work for a living in capitalist society is legally enforced and regulated by the statee, for example through workfare and strict conditions for receiving an unemployment benefit.

Although capital accumulation does not necessarily require production, ultimately the basis for it is value-adding production which makes net additions to the stock of wealth. Capital can accumulate by shifting the ownership of assets from one place to another, but ultimately the total stock of assets must increase. Other things being equal, if production fails to grow sufficiently, the level of debt will increase, ultimately causing a breakdown of the accumulation process when debtors cannot pay creditors.

Capital accumulation does not necessarily require trade either, although capital presupposes trade, and the ability to exchange goods for money. The reason is that wealth can be amassed through illegal or legalised expropriation (robbery, plunder, theft, piracy, slavery, embezzlement, fraud and so on). However, a continuous and cumulative accumulation process always presupposes that capital ownership is secure. Consequently, military and police forces have typically been necessary for capital accumulation on a larger scale, to protect property.

In medieval society, typically the bourgeoisie could not protect its capital assets permanently from attacks, which meant that the accumulation process was interrupted, and remained limited in scope. Today however, capitalists can own billions of dollars worth of assets which are well-protected against crime (see the annual Merrill-Lynch survey of the world's wealthy). With the aid of private banking it is easier to obscure or hide the wealth that one owns.

Regime of accumulation

Both the Regulation School of French Marxist economists, inspired by the original writings of Michel Aglietta and developed by Robert S. Boyer, as well as the American social structure of accumulation school founded by the economists Samuel Bowles and David Gordon have emphasized that the processes of capital accumulation occur within a social regime of accumulation.

In other words, a specific political and socio-economic environment is required that enables sustained investment and economic growth. This environment is created partly by state policy, but partly by also by technological innovations, changes in popular culture, commercial developments, the media, and so on. An example of such a regime often cited here is that of Fordism, named after the enterprise of Henry Ford. As the pattern of accumulation changes, the regime of accumulation also changes.

Similar ideas also surface in institutional economics. The main insight here is that market trade cannot flourish without regulation by a legal system plus the enforcement of basic moral conduct and private property by the state. But the regime of accumulation responds to the total experience of living in capitalist society, not just market trade.

Environmental criticisms

The environmental criticism of capital accumulation focuses on four main ideas.

Firstly, there is the problem of externalities. This means that public or privately owned industry incurs costs, including environmental and health costs, which are not charged or priced. This happens for example when effluents are discharged on land, water or in the air, which can cause pollution or despoilation of terrains. In recognition of this, environmental taxes are sometimes imposed.

Secondly, commercial activities which may be rational from the point of view of a narrow public or private enterprise may not be rational from the point of view of the larger society, or from the point of view of the biosphere, especially when they involve the destruction of natural habitats of flora and fauna, pollution and entropy.

Because a natural resource happens to be a freely available good (for example fish in the open sea), it may be over utilized by either public or private enterprises. Or, a lot of energy may be wasted producing and transporting a good to the consumer. Or, the disturbance of subsistence economics by commerce may cause overpopulation by not controlling population by starvation.

Thirdly, goods and services may be produced for public or private profit in ways which are directly or indirectly harmful to human life, either because of the nature of the use-value involved, or because of the techniques used to produce them, or because they encourage consumer habits with harmful effects.

Finally, business and cultural ethics may often not be reconcilable with some human ethics or good environmental ethics. This means for example that the imputation of a price to an environmental cost, or imposing an environment tax may be insufficient as a policy, because some things which have value simply have no price.

Nowadays environmental concerns are an essential part of so-called socially responsible business and corporate governance. However, opinion is divided about whether a capitalist market economy can be ecologically sustainable. Some argue that the experience of wide spread environmental destruction in the Soviet Union and China proves that state socialism or command economy can be ecologically worse than capitalism. Today [2005] some environmentalists consider capitalism, or the "free market system" as it is usually called, incapable of complying with the basic requisites of a sustainable and respectful habitation of planet earth. A major problem, inherent in some free market production dynamics, is the constant desire to constantly expand production. In this particular regard, critics point to the penchant to plan in short-term cycles, and with a narrow concern about the fortunes of only a single country, firm or business entity, thereby ignoring the cumulative effect brought to bear on the biosphere by the entire production system.

In the 1970s, some environmentalists argued for a policy of'"zero economic growth" in "affluent" Western societies. However, when a long recession began in that decade, halving economic growth rates, most people became more concerned about mass unemployment. Thus, the proponents of zero growth lost popularity. Nowadays, the popular concept is sustainable economic development or growth. But interpretations of what that means can differ wildly. One difficulty is that predictions of future resource scarcity are usually based on extrapolation from the past, "assuming present trends will continue", but they may not.

Capital accumulation and risk

Most capital accumulation involves risk, because capital is committed to an investment without perfect certainty of future earnings. A capital asset could gain value, but it could also lose value in the future. Owners of capital (investors) therefore typically diversify their investment portfolio, and try to minimise the risks involved in investments by every possible means.

In the course of two centuries of capital accumulation based on industrialisation the intensive economising and exploitation of human labour, and technological innovation,

- the value of the assets that are invested in has become very large

- the markets traded in extend around the globe

- the deregulation of markets has increased the level of market uncertainty

- the volume of speculative capital has grown enormously

- the banking industry dominates the ownership of capital assets.

This has led to an enormous expansion of the insurance industry and of the profession of risk management. As a corollary, this powerfully stimulates the construction of mathematical models which aim to assess how probable it is that particular "risky events" will occur. Some sociologists such as Frank Furedi claim that an exaggerated and unhealthy preoccupation or anxiety about risks has infiltrated the whole of modern society.

Speculation - making money from price differentials or price fluctuations - is justified as follows: "The roles of speculators in a market economy are to absorb risk and to add liquidity to the marketplace by risking their own capital for the chance of monetary reward." However, speculation often also occurs with borrowed capital. In this case, capital is borrowed at a low rate of interest, and reinvested at a higher return.

Capital accumulation and military wars

Wars typically causes the diversion, destruction and creation of capital assets as capital assets are both destroyed or consumed and diverted to types of production needed to fight the war. Many assets are wasted and in some few cases created specifically to fight a war. War driven demands may be a powerful stimulus for the accumulation of capital and production capability in limited areas and market expansion outside the immediate theatre of war. Often this has induced laws against perceived and real war profiteering.

War destruction can be illustrated by looking at World War II. Industrial war damage was heaviest in Japan, where 1/4 of factory buildings and 1/3 of plant & equipment were destroyed; 1/7 of electric power-generating capacity was destroyed and 6/7 of oil refining capacity. The Japanese merchant fleet lost 80% of their ships. In Germany in 1944, when air attacks were heaviest, 6.5% of machine tools were damaged or destroyed, but around 90% were later repaired. About 10% of steel production capacity was lost. In Europe, the United States and the Soviet Union enormous resources were accumulated and ultimately dissipated as planes, ships tanks, etc. were built and then lost or destroyed.

Germany's total war damage was estimated at about 17.5% of the pre-war total capital stock by value, i.e., about 1/6. In the Berlin area alone, there were 8 million refugees lacking basic necessities. In 1945, less than 10% of the railways were still operating. 2395 rail bridges were destroyed and a total of 7500 bridges, 10,000 locomotives and more than 100,000 goods wagons were destroyed. Less than 40% of the remaining locomotives were operational.

However, by the first quarter of 1946 European rail traffic, which was given assistance and preferences (by western appointed military governors) for resources and material as an essential asset, regained its prewar operational level. At the end of the year, 90% of Germany's railway lines were operating again. In retrospect, the rapidity of infrastructure reconstruction appears astonishing.

Initially, in May 1945, newly installed U.S. President Harry S. Truman's directive had been that no steps would be taken towards economic rehabilitation of Germany. In fact, the initial industry plan of 1946 prohibited production in excess of half of the 1938 level; the iron and steel industry was allowed to produce only less than a third of pre-war output. These plans were rapidly revised and better plans were instituted. In 1946, over 10% of Germany's physical capital stock (plant & equipment) was also dismantled and confiscated, most of it going to the USSR. By 1947, industrial production in Germany was at 1/3 of the 1938 level, and industrial investment at about 1/2 the 1938 level.

The first big strike wave in the Ruhr occurred in early 1947 - it was about food rations and housing, but soon there were demands for nationalisation. The U.S. appointed military Governor (Newman) however stated at the time that he had the power to break strikes by withholding food rations. The clear message was: "no work, no eat". As the military controls in Western Germany were nearly all relinquished and the Germans were allowed to rebuild their own economy with Marshal Plan aid things rapidly improved. By 1951, German industrial production had overtaken the prewar level. The Marshall Aid funds were important, but, after the currency reform (which permitted German capitalists to revalue their assets) and the establishment of a new political system, much more important was the commitment of the USA to rebuilding German capitalism and establishing a free market economy and government, rather than keeping Germany in a weak position. Initially, average real wages remained low, lower even than in 1938, until the early 1950s, while profitability was unusually high. So the total investment fund, aided by credits, was also high, resulting in a high rate of capital accumulation which was nearly all reinvested in new construction or new tools. This was called the German economic miracle or "Wirtschaftswunder".[4]

In the United States in World War II the large investments in industrial plant necessitated by the war brought some advantages; but the costs of dead, waste and debt would have never been undertaken by any rational government for the slight advantages.

In modern times, it has often been possible to rebuild physical capital assets destroyed in wars completely within the space of about 10 years, except in cases of severe pollution by chemical warfare or other kinds of irreparable devastation. However, damage to human capital has been much more devastating, in terms of fatalities (in the case of World War II, about 55 million deaths), permanent physical disability, enduring ethnic hostility and psychological injuries which have effects for at least several generations.

New developments in capital accumulation

New trends in capital accumulation include:

- financialisation (the extraordinarily strong growth of the international financial markets. This is trade in financial claims to current and future income. As a corollary, the proportion of national income which consists of interest income and rentier income increases. The International Swaps and Derivatives Association reported in September 2006 that the outstanding nominal value of swaps and derivatives at the end of June 2006 was $283 trillion - nearly ten times the combined GDP of the US, Canada, the EU, Japan, and China; or ten times the value of total US home equity (each being valued at about $34 trillion). According to Standard & Poor's, world stock market capitalization is about $41 trillion. Of total swaps and derivatives, some $26 trillion was in the fastest growing area, credit default swaps.

- Modern information technology makes it possible to engage in very complex investment projects and shift funds extremely quickly from one placement to another in space and time. This increases the rotation speed of capital and raises the profit rate, but can also increase potential financial risks.

- the growing controversies about intellectual property rights and the protection (or security) of ideas which can make money for the owner. Increasingly, the basic conditions necessary for a good, service or idea to become a tradeable commodity are theoretically defined.

- ongoing privatisation of assets which were previously under public ownership. The IMF estimates suggest that in two decades since 1985 more than $2 trillion US dollars (in 2005 values) worth of state assets were privatised worldwide. Typically, these assets also rise sharply in value within a few years, because they involve enterprises occupying monopoly positions (e.g., utilities) which thus provide guaranteed profits. If profits dry up in the private sector, capitalists acquire public assets paid for by all citizens, with the argument that if they run them, supply will be more efficient.

- The enormous increase in capital gains from rising property values in the richer countries, especially in the |housing market. US tax data for fiscal 2000 showed that realised capital gains in the USA peaked at an estimated $644.3 billion worth of income while US GDP in 2000 was at US$9,817.0 billion, in other words realised capital gains assessed for tax purposes were equal to 6.5% of GDP at that point (total capital gains would be larger). Yet GDP, being a measure of value added in production, does not even include this "hidden" personal and business income.

- A growing proportion of capital assets which is not productively invested (overcapitalisation), together with an increase in the amount of consumer debt and liabilities. Some observers see the cause as being an increase in the gap between rich and poor, which causes only sluggish demand growth. "Debt management" has become a distinct and profitable business.

- The crisis of numerous pension funds providing a large amount of investment capital, which are alleged to be badly managed.

- An international "competition of currency values" strongly influenced by speculative capital, which has a big effect on the pattern of international trade. The magnitudes involved can be gauged, e.g., from the currency conversion ratios used to establish purchasing power parity (PPP). For example, India's GDP valued at PPP becomes five times larger. This tends to stimulate counter-trade.

- The acceleration of the concentration and centralisation of capital internationally in very large corporations. The Fortune Magazine "Global 500" largest corporations in 2004 employed more people than the whole workforce of Germany. The after-tax profit volume of the Fortune Global 500 was said to be $731 billion, the combined asset value was $60.8 trillion, gross income (revenues) $14.8 trillion, and stockholders equity $6.8 trillion. For comparison, world GDP in 2004 was valued at $40.9 trillion (World Bank).

- The Merrill lynch/CapGemini World Wealth Report 2005 covering High Net Worth Individuals (HNWI) claims the fortunes of the world's millionaires and billionaires grew strongly in 2004, increasing by 8.2% to US$30.8 trillion in one year. Driven by North America & Asia–Pacific, this represents "the highest growth of HNWI wealth in more than three years".

- Dollarisation - more US currency now circulates outside the US than inside it, and some countries such as Ecuador and El Salvador have adopted the US dollar as national currency. "Dollar hegemony" is maintained by large Asian, Arab and European investments in the United States.

- the tendency for corporate investment to orient towards activities which secure good short-term returns for shareholders. This is called "value-based management". Most corporate executive officers (CEO's) cite profitability as their prime concern.

- an increasing preoccupation with the conditions for extending credit, and with all sorts of risk factors. World markets are increasingly sensitive to events and disturbances which might cause social instability or panics.

- the declining overall significance of business start-ups, in the sense of enterprises creating new products and services, rather than being just tax-shelters or secondary employment (whether this is a permanent trend remains to be seen).

- the growth of criminal (or illegal) accumulation as measured by crime reports, including business crime and corruption such as fraud, embezzlement, money laundering, insider trading, smurfing and theft, but also prostitution, forced labour, slavery, war plunder etc. The volume of illegal international transactions is now said to be around $1 trillion a year, equal to the GDP of Spain or Canada. National Geographic has reported there are about 27 million slaves in the world. International Labour Organization estimates of forced labor are a little over a dozen million. There are possibly 70 million people involved around the world in prostitution of one form or another. But there are many more, employed or unemployed, in "intermediate" positions. Traditional sociological categories may not describe their situation accurately, but a growing "underclass" (which may not be an accurate label) is a policy concern for many governments.

- the most ignored aspect is the changing structure of the international workforce in its totality, specifically the number employed by specific employment status and by income, in different sectors. But just as Marx's Law of Accumulation predicted, the working class has grown enormously within 2 centuries. Deon Filmer estimated that 2,474 million people participated in the worldwide non-domestic labour force in the mid-1990s. Of these around a fifth, 379 million people, worked in industry, 800 million in services, and 1,074 million in agriculture. The majority of workers in industry and services were wage & salary earners - 58 percent of the industrial workforce and 65 percent of the services workforce. But a big portion were self-employed or involved in family labour. Filmer suggests the total of employees worldwide in the 1990s was about 880 million, compared with around a billion working on own account on the land (mainly peasants), and some 480 million working on own account in industry and services.

- tax havens. Hides 8 trillion.

See also

References

- ^ [1] Definition of Capital on Marxists.org

- ^ Karl MARX. "Das Kapital, ch.25". http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch25.htm. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ^ [2] "Das Kapital", vol.1, ch. 25

- ^ Armstrong, Glyn & Harrison 1984

A few references to works of theory

- Michel Aglietta, A Theory of Capitalist Regulation.

- Elmar Altvater, Gesellschaftliche Produktion und ökonomische Rationalität; Externe Effekte und zentrale Planung im Wirtschaftssystem des Sozialismus.

- Samir Amin, Accumulation on a world scale.

- Philip Armstrong, Andrew Glyn and John Harrison, Capitalism since World War II.

- Paul A. Baran, The Political Economy of Growth.

- Gregory Clark (economist) A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World.

- P. Groenewegen (ed.), Economics and ethics.London: Routledge 1996.

- Henryk Grossman, The Law of Accumulation and Collapse of the Capitalist System.

- Andre Gunder Frank, World accumulation, 1492 - 1789. New York 1978

- Rudolf Hilferding, Finance Capital.

- Rosa Luxemburg, The Accumulation of Capital.

- Ernest Mandel, Marxist Economic Theory.

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital Vol. 1, Part 7 and Vol. 2, Part 3.

- Seymour Melman, Profits without production.

- Michael Perelman, Steal this Idea: the Corporate Confiscation of Creativity.

- Joan Robinson, Essays in the Theory of Economic Growth.

- Harry Rothman, Murderous providence; A study of pollution in industrial societies.

- Vaclav Smil, China's Environmental Crisis: An Inquiry into the Limits of National Development. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1992.

- Hernando de Soto, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else.

- Manual Velázquez, Business Ethics: Concepts and Cases.

- William J. Bernstein, The Birth of Plenty: How the Modern World of Prosperity was Launched.

- Deon Filmer, Estimating the World at Work, a background report for World Bank's World Development Report 1995 (Washington DC, 1995).

- Willem van Schendel and Itty Abraham (eds), Illicit Flows and Criminal Things. States, Borders, and the Other Side of Globalization. Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2005; ISBN 0-253-34669-X

- Joshua S. Goldstein, War and economic History [3]